What is the circular economy?

The term circular economy is showing up everywhere — from sustainability strategies to EU policy and innovation hubs. But what is it, really?

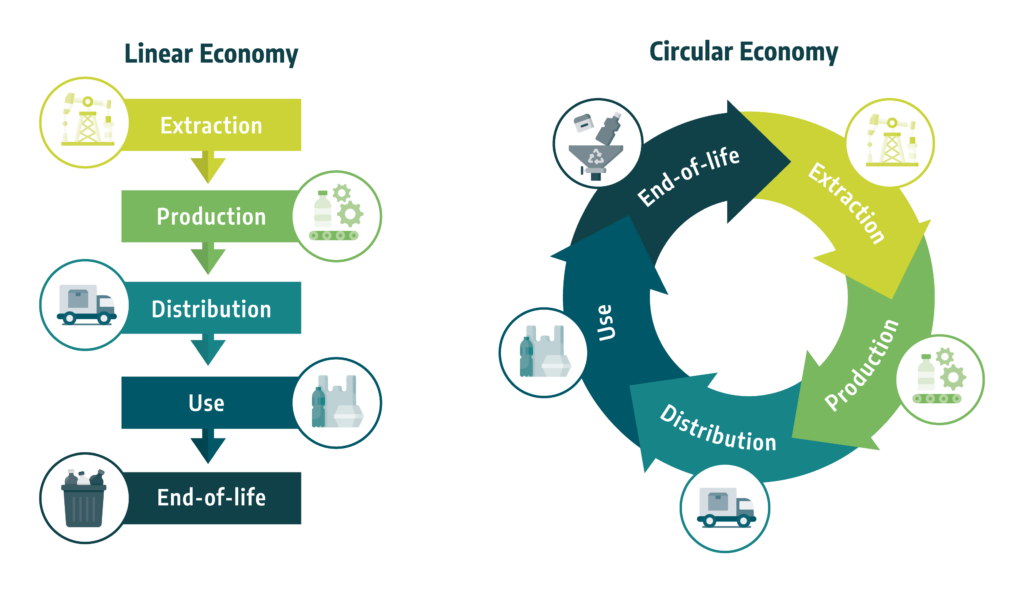

At its heart, the circular economy is an economic model that focuses on redesigning the way we live, produce, and consume. It moves away from the outdated linear model of take, make, dispose and instead builds a system where materials are used smarter, for longer, and with less impact. (Circular Economy Introduction, n.d.)

The Three Core Principles of Circular Economy:

🔁 Design out waste and pollution:

Circular design means thinking about a product’s entire lifecycle from the start. This includes choosing materials that are renewable, recyclable, or biodegradable, and creating packaging or products that are easy to disassemble, repair, or reuse. It also means eliminating harmful substances and designing in ways that reduce carbon emissions and pollution before they even happen.

🔧 Keep products and materials in use:

Rather than seeing materials as disposable, this principle pushes us to maximize the value of everything we produce. That means repairing instead of replacing, reusing instead of discarding, and recycling when reuse isn’t possible. It’s about closing loops — so that packaging, for example, becomes a resource, not a waste.

🌱 Regenerate natural systems:

Beyond reducing harm, the circular economy actively seeks to restore nature. Through regenerative agriculture, composting, and circular food systems, the idea is to support biodiversity, enrich soils, and enable ecosystems to thrive. It’s a shift from extraction to renewal — ensuring that economic activity gives back more than it takes.

(Circular Economy Introduction, n.d.)

Together, these three principles form the foundation of a truly circular economy — one that rethinks how we design, use, and relate to the materials around us. By designing out waste, keeping resources in circulation, and regenerating the natural world, we can build systems that are not only more sustainable but also more resilient, innovative, and equitable. The shift to circularity isn’t just an environmental imperative — it’s a powerful opportunity to create a thriving future for people and the planet alike.

Why It Matters for Food Packaging

In particular within food packaging, the circular economy isn’t just a theoretical concept — it’s a practical and urgent solution to some of the most pressing environmental and economic challenges of our time. And food packaging is one of the clearest examples of how the linear economy is failing us. Most packaging today is single-use, made from fossil-based plastics or aluminum, and quickly turns into waste — polluting our land, waterways, and even our bodies through microplastics.

It’s also energy-intensive, difficult to recycle, and often contaminated after use — turning every snack wrapper or takeaway container into a long-term environmental burden.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY 3.0

The good news? A circular approach offers real, tangible solutions — especially in the realm of food packaging, one of the biggest contributors to global waste. By rethinking how we design, use, and dispose of packaging, we can drastically reduce pollution, conserve resources, and support healthier ecosystems.

In a circular system, food packaging is no longer treated as single-use waste but as a valuable material that can stay in use. For instance, some companies are adopting refill and return models, where consumers can bring reusable containers to stores or have products delivered in packaging that’s collected, cleaned, and reused. Others are experimenting with edible packaging made from seaweed, starches, or rice paper — solutions that disappear after use and leave no trace.

Photo by Anna Tarazevich (Pexels), licensed under CC0

Compostable materials are also gaining traction. These can include packaging made from agricultural by-products like sugarcane fiber or corn husks, which break down into nutrient-rich compost under the right conditions. In some cities, closed-loop composting systems are being introduced, where food scraps and compostable packaging are collected together and returned to farms as soil enhancers — turning waste into a resource that feeds the next crop.

Even traditional packaging materials are being redesigned for circularity. Some manufacturers are developing monomaterial films — packaging made from a single type of plastic that’s easier to recycle — or using transparent labeling to guide consumers on how to dispose of items properly.

These examples show that circular food packaging isn’t just a future idea — it’s already happening, and it’s working. When designed thoughtfully, packaging can protect food and the planet, while also creating new economic opportunities in reuse, recycling, and composting industries.

Applicability Challenges: The Roadblocks to Circularity (and Why It’s Still Worth It)

Transitioning to a circular economy isn’t easy. It requires systemic change — from how products are designed to how consumers interact with them. But despite the hurdles, the benefits are too important to ignore.

⚠️ Key challenges:

Higher upfront costs: Transitioning to circular materials, product designs, and business models often requires significant initial investment. For producers, this can include redesigning products for longevity or modularity, investing in take-back schemes, or sourcing more sustainable materials, which are often more expensive than conventional alternatives. Consumers may also face higher prices for durable or refillable products, which can act as a barrier to widespread adoption.

Lack of infrastructure: Effective circular systems rely on robust infrastructure for collection, sorting, reprocessing, and redistribution of materials. However, in many regions — especially in developing economies — these systems are either underdeveloped or nonexistent. Without adequate logistical networks and recycling facilities, materials often end up in landfills or incinerators, undermining circular goals.

Behavioural shifts: The success of circularity depends heavily on consumer participation. This includes habits like returning used products, refilling containers, separating waste properly, or choosing refurbished goods. Encouraging these behaviours requires time, education, incentives, and sometimes a cultural mindset shift. Without widespread consumer engagement, circular systems struggle to operate effectively.

Policy gaps: Legislation and regulatory frameworks frequently lag behind technological advancements in circular economy practices. This can create uncertainty for businesses looking to innovate and invest. Inconsistent policies across regions, a lack of clear standards, and inadequate incentives can all hinder the development of circular initiatives, leaving innovators navigating legal grey areas.

✅ Why it’s still worth it:

Lower environmental impact: Circular systems reduce the extraction of virgin resources, limit greenhouse gas emissions, and cut down on waste sent to landfills or oceans. By designing waste out of the system and keeping materials in use, circularity addresses some of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time, including biodiversity loss and climate change.

Long-term savings: While the initial investment may be high, circular models often lead to cost savings over time. Reusing materials, extending product lifecycles, and optimizing resource flows can reduce operating costs, minimize waste disposal fees, and unlock new revenue streams. For consumers, durable and repairable products can offer better value over the long run.

Room for innovation: The shift toward circularity opens doors for creative problem-solving. Businesses are exploring new service-based models (like product-as-a-service), developing biodegradable or infinitely recyclable materials, and using AI or blockchain for supply chain transparency. This innovation fosters competitiveness and can lead to entirely new industries.

Greater resilience: By reducing dependence on finite raw materials and globalized supply chains, circular systems can buffer against disruptions — whether due to geopolitical instability, supply shortages, or environmental disasters. A more localized, closed-loop approach increases economic and environmental resilience, making systems more robust in the face of future challenges.

(Circular Economy: Definition, Importance and Benefits | Topics | European Parliament, n.d.)

MAGNO: Circular Solutions in Action

The MAGNO Project is at the forefront of making the circular economy a reality in the food packaging value chain. By putting circular principles at the center of the food packaging value chain, MAGNO is helping reshape how packaging is designed, used, and reused.

Whether it’s through promoting business models based on reuse and return or leveraging AI to improve decision-making along the supply chain — MAGNO is working with manufacturers, researchers, and policymakers to create a system where food packaging stops being a problem and starts becoming part of the solution.

Beyond Packaging: Why It Matters More Than You Think

While food packaging is a highly visible area, the circular economy touches every sector — from textiles and electronics to agriculture and construction. It’s a chance to transform entire industries into systems that are more efficient, resilient, and future-ready.

But the truth is: sustainability isn’t just about buying sustainable products. The most impactful choice we can make is often to consume less in the first place. If we do need to buy, we should ask:

Do I really need this? Is it reusable? Is it supporting a circular system?

In the end, circularity challenges us to rethink not just what we consume, but why. It’s a call for smarter, more intentional choices — from individuals, industries, and institutions alike. It’s about reimagining how we create value, how we interact with the world around us, and how we build a future that thrives without costing the Earth.

🌀 Curious to learn more? Check out MAGNO’s Practice Abstract 2: MAGNO’s Circular Approach for the Food Packaging Value Chain – MAGNO-PROJECT to dive into the strategies driving this transition.